A Lasting Impact: COVID-19 and Cancer Screening

Several years after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, labs are still dealing with the effects of missed and delayed screenings

In early 2020, when the COVID-19 pandemic threatened to overwhelm healthcare services, many countries put routine procedures like cancer screenings on the back burner. Even after the situation stabilized, many healthcare providers faced massive waiting lists—and patients were often hesitant to return to settings they perceived as unsafe for procedures they considered optional. The outcome of this was a drastic reduction in patients receiving timely evaluation for conditions like cervical, colorectal, and prostate cancer. Now, several years on, most screening programs have returned to their regular volumes—but the pandemic’s impact continues to be felt.

Initial impact

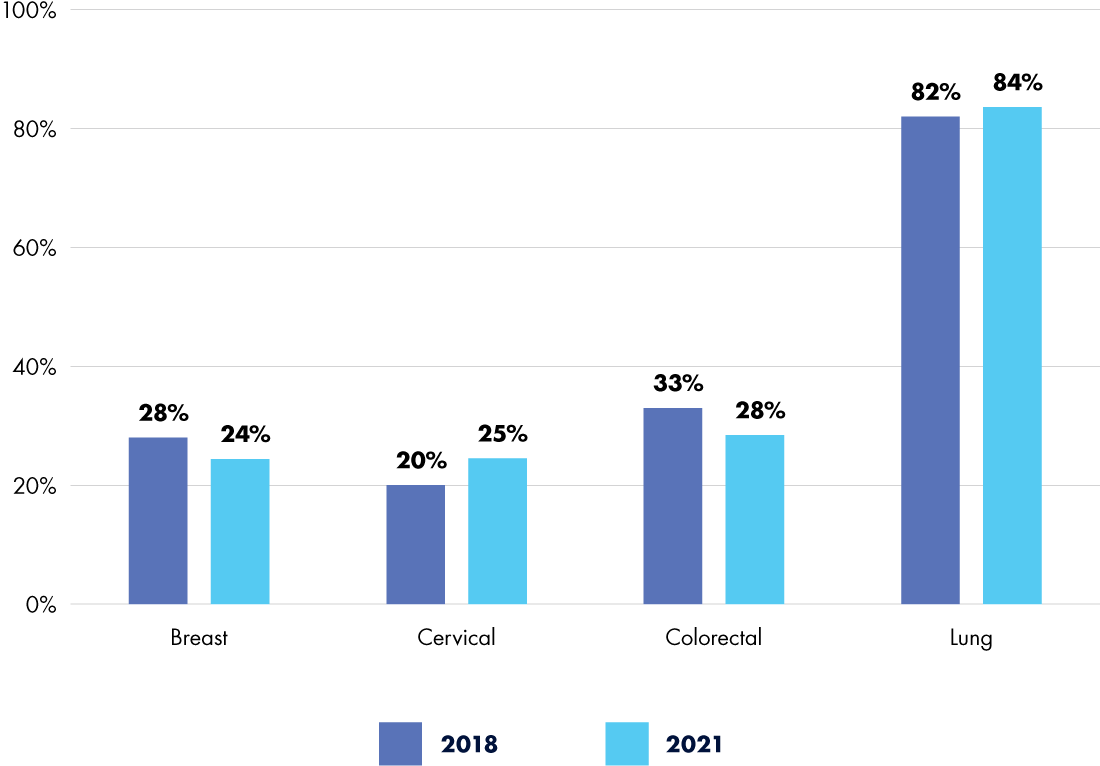

Even prior to 2020, cancer screening uptake was suboptimal and health inequities were high. In 2018, the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) reported that significant percentages of eligible individuals were not up to date with recommended screenings: 28 percent for breast cancer, 20 percent for cervical cancer, 33 percent for colorectal cancer, and a staggering 82 percent for lung cancer.1 Despite steady gains in the years preceding the pandemic, by 2021, those numbers had only just returned to their 2018 levels2—with some showing marginal improvements, but others worsening (see Figure 1).

The pandemic’s effect on screening numbers is undeniable. Globally, research suggests that all major cancer screenings dropped significantly between January and October of 2020, with attendance decreasing 46.7 percent, 44.9 percent, and 51.8 percent for breast, colorectal, and cervical cancer screenings, respectively.3 With 9.4 million people in the United States estimated to have missed screenings in the first three months of the pandemic alone,4 it’s no surprise that labs and healthcare systems continue to experience the knock-on effects of missed and delayed testing.

Ongoing effects

For many labs, screening backlogs are still driving up workloads for already stressed staff. This is particularly true in resource-limited settings, where people in low-income neighborhoods, older age brackets, or First Nation communities are more likely to experience diagnostic delays following screening.5 In 2021, the latest year for which complete data exist, screening disparities still loomed large—especially those based on race and ethnicity, income, education, disability, and insurance status. People with private health insurance were more than twice as likely to be screened for colon cancer as uninsured patients, three times as likely to be screened for prostate cancer, and five times as likely to be screened for lung cancer.2

For some eligible patients, forgoing cancer screening at the height of the pandemic meant that they were lost to follow-up. In Ontario, Canada, for example, over 20 percent of women eligible for cervical cancer screening never receive a mailed invitation due to missing or incorrect contact details;6 the increase in relocations and housing loss as a result of COVID-19 is expected to have further exacerbated this issue, especially for patients who face other barriers to screening.5

Even more significant than the burden of backlogged screening is the population of patients who have received, or will receive, a late cancer diagnosis due to pandemic-related screening disruptions. Late diagnoses may lead to limited treatment options, more complex—and costly—care, lower survival rates, and worse outcomes for patients. One study on five common cancers in Chile projected a drop in overall diagnoses due to competing COVID-19 mortality, but a change in stage distribution at diagnosis that would yield about 3,500 excess deaths7—over 10 percent of the country’s total annual cancer mortality.8

Although studies indicate that overall cancer diagnostic rates have returned to expected levels, this recovery is not enough to address the diagnostic deficit that remains. In addition, detailed statistics show that certain cancers—notably ones with established screening guidelines and programs, such as melanoma, lung, and prostate cancer—have the largest cumulative deficit,9 suggesting that new approaches to improving screening uptake are urgently needed to alleviate inequities and ensure timely diagnosis and treatment for all patients.

Innovative interventions

Screening program successes and failures during the pandemic’s peak offer insights into increasing patients’ engagement. A survey of people who delayed a scheduled cancer screening between March and December of 2020 revealed that tests requiring more complex procedures were more likely to be postponed. In particular, colonoscopies (36.2 percent delayed), cervical smears (27.1 percent), and human papillomavirus tests (26.8 percent) topped the list, with stool blood tests (11.3 percent delayed) at the opposite end of the spectrum.10 Testing methods that reduce time, travel, or expense—such as multi-screening appointments, mobile laboratories, or at-home self-sampling kits—increase the likelihood that patients will pursue screening. Combining these strategies with targeted outreach and education in communities that are more likely to delay screening can further improve engagement.

The lab’s role

What can clinical laboratory professionals do to help? Although much of the necessary intervention rests in the hands of primary care providers, laboratorians can be instrumental in educating not only these providers, but also their patients on the value of regular screening and early disease diagnosis.11 By participating in the design and refinement of screening programs, lab professionals can ensure that testing is as efficient, effective, and appropriate as possible. Interacting directly with patients can also demystify the lab and its role in patients’ health, alleviate anxiety and misunderstandings surrounding tests, uncover unmet needs in patient-centered laboratory care, and raise public awareness of the importance of cancer screening.

Current efforts to increase uptake include leveraging electronic health records to identify patients in need of screening or follow-up, increasing the use of decentralized and mail-in testing, tailoring educational material to specific communities, and exploring new technological options for earlier and less invasive cancer detection.12 Coupled with efforts to grow the clinical laboratory workforce and streamline workflows, screening targets aimed at reducing the healthcare burden of cancer and extending patients’ lives may be well within reach.

References:

- American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Progress Report 2021. November 1, 2021. https://cancerprogressreport.aacr.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/10/AACR_CPR_2021.pdf.

- American Association for Cancer Research. AACR Cancer Progress Report 2024. September 18, 2024. https://cancerprogressreport.aacr.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2024/09/AACR_CPR_2024.pdf.

- Teglia F et al. Global association of COVID-19 pandemic measures with cancer screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2022;8(9):1287–1293. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.2617.

- Chen RC et al. Association of cancer screening deficit in the United States with the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(6):878–884. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.0884.

- Walker MJ et al. Measuring the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on organized cancer screening and diagnostic follow-up care in Ontario, Canada: a provincial, population-based study. Prev Med. 2021;151:106586. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106586.

- Clark M et al. Limitations in correspondence programs for cervical cancer screening: who are the women we are missing? J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41(10):1410–1415. doi:10.1016/j.jogc.2018.11.034.

- Ward ZJ et al. Estimating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on diagnosis and survival of five cancers in Chile from 2020 to 2030: a simulation-based analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(10):1427–1437. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00426-5.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Chile. Global Cancer Observatory. February 8, 2024. https://gco.iarc.who.int/media/globocan/factsheets/populations/152-chile-fact-sheet.pdf.

- Kim U et al. Recovery from COVID-19-related disruptions in cancer detection. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(10):e2439263. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.39263.

- Zhang X et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer screening delays. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41(17):3194–3202. doi:10.1200/JCO.22.01704.

- Toth JF 3rd et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: the role of clinical laboratories. Clin Chem. 2024;70(1):150–164. doi:10.1093/clinchem/hvad198.

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Screening Research Network (CSRN). February 21, 2024. https://prevention.cancer.gov/major-programs/cancer-screening-research-network-csrn.

Subscribe to Clinical Diagnostics Insider to view

Start a Free Trial for immediate access to this article