AACC Offers New Guidance for HPV and Cervical Cancer Screening

New document aims to help clinicians navigate screening guidelines, choose testing strategies, and analyze test results.

Cervical cancer screening has made enormous strides since the invention of the Pap smear, with the advent of technologies such as HPV testing and liquid-based cytology. Meanwhile, some of the country’s largest and most influential medical associations have issued guidelines recommending novel and aggressive testing strategies. While these are all positive developments, they have also engendered some degree of confusion and misunderstanding, leading the American Association for Clinical Chemistry (AACC) to publish new guidance on navigating these guidelines, deciding on testing strategies, and analyzing test results.1

The Diagnostic Challenge

Cervical cancer remains the fourth most prevalent form of cancer among women, accounting for 604,000 new cases and 342,000 deaths worldwide in 2020, according to the World Health Organization.2 Before 2023 ends, 13,960 US women will be diagnosed with and 4,310 will die of cervical cancer, according to American Cancer Society estimates.3

At one time, cervical cancer was among the most common causes of cancer death for American women.4 As with most cancers, early detection is the key to improving cervical cancer mortality and outcomes. Thus, cervical cancer death rates have dropped significantly in recent decades thanks to the introduction and widespread use of the Pap test, also known as cervical cytology, which detects changes in the cells collected from the cervix before cancer develops.

The leading cause of most cervical cancers is infection with human papillomavirus (HPV). Two high-risk forms of HPV are responsible for approximately 70 percent of cervical cancers—type 16 and type 18.2 As a result, many medical organizations recommend screening for cervical cancer with either primary HPV testing, or by co-testing with both the Pap and HPV test. Three major organizations have published guidelines recommending these new approaches: the American Cancer Society (ACS) in 2020,5 the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) in 2019,6 and the United States Preventative Services Task Force (USPSTF) in 2018.7

The AACC Guidelines

However, the AACC notes that these current guidelines contain “nuanced differences” that could make it difficult to determine the most effective testing strategy for cervical cancer detection. Published in The Journal of Applied Laboratory Medicine on March 6, 2023, the AACC guidance seeks to highlight and explain the differences among the ACS, ASCCP, and USPSTF guidelines to enable medical professionals and laboratories to make more informed decisions in light of the latest testing developments.

To establish the basis for an apples-to-apples comparison, the AACC guidance notes that cervical cancer tests are used for three broad purposes, which are often perceived as interchangeable but, in fact, have important distinctions:

-

- Screening, or testing of asymptomatic women who have not been tested before or are not deemed at particularly high risk as a proactive prevention measure

-

- Surveillance, or testing at regular intervals of women who have had a prior abnormal test result

- Diagnosis, including biopsy and colposcopy of women who exhibit bleeding, discharge, pain, or other symptoms of cervical cancer

The AACC stresses that there are currently no randomized trials comparing mortality rates among the different testing strategies recommended by the ACS, ASCCP, and USPSTF. “This means that certain decisions about cervical cancer screening should be based on informed discussions with the patient, while other decisions can be made based on what works best for an institution,” according to the press statement the AACC released with the new guidance.8

For example, although some studies9 have found co-testing is more beneficial than HPV testing alone, AACC says that use of HPV testing alone for screening, also known as primary HPV screening, performs just as well as and at less cost than a co-testing approach relying on molecular testing and cytology.9 As a result, “institutions can screen with HPV testing alone if they have an HPV test that is FDA-approved for primary screening, while institutions with one of the other HPV tests can continue to use co-testing.”

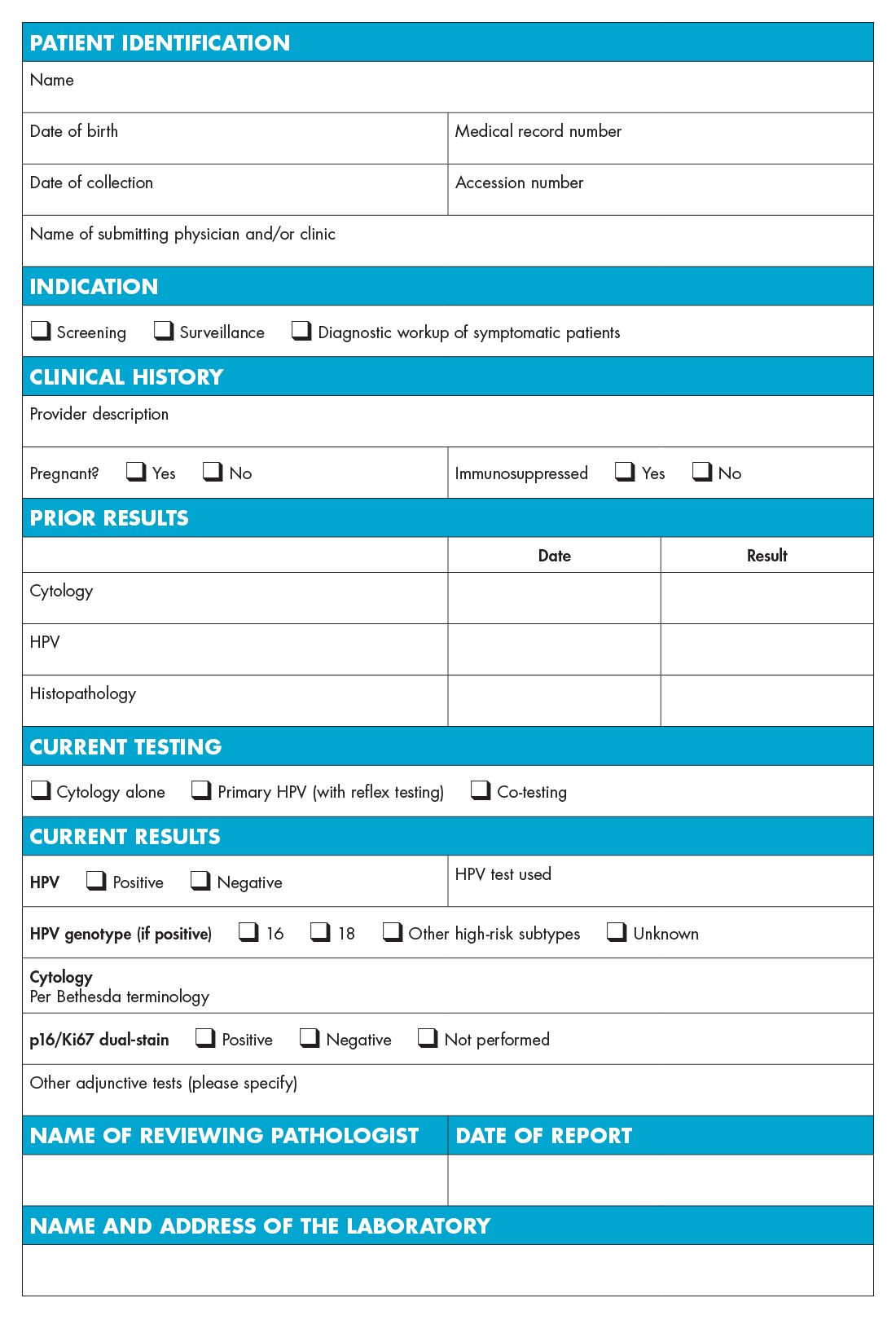

The Ideal Laboratory Report

After comparing the guidelines, the AACC incorporated a summary of the results into a template of an “ideal lab report” that clinicians can use in deciding on HPV and cervical cancer testing and analyzing test results. “While this template can be modified for local needs, we believe it incorporates the most important components,” the authors note.

HPV & Cervical Cancer Testing Report Template

Molecular HPV Tests Approved by the FDA

Self-Collected Samples for HPV Testing

Although it is not yet FDA-approved or currently the standard of care in the US, the AACC guidance suggests that use of self-collected vaginal specimens for HPV testing could improve cervical cancer detection among underscreened populations. Recent studies addressing the stability of these samples and how they perform compared to samples collected by laboratory technicians show that, though HPV testing done on self-collected samples has a much lower positive predictive value when compared with cytology, it may be a better option in low-resource settings.

The Future of Cervical Cancer Testing

AACC’s new guidance also explores recent trends that may help make it easier to implement cervical cancer testing guidelines, as well as make such testing more accessible in the future. Such developments include the increased use of test result automation and standardization, making it easier to estimate a patient’s risk of developing cancer, as well as better track results and remind patients of testing appointments.

More research data and HPV assays becoming available could increase the number of FDA-approved tests for primary HPV testing. The AACC concludes that this type of HPV testing may help make screening more accessible to certain communities, as it is better suited to self-collection, has been shown to perform better than cytology alone, and is cheaper than co-testing, while offering similar performance.

References:

Subscribe to Clinical Diagnostics Insider to view

Start a Free Trial for immediate access to this article