How the Roe v. Wade Ruling Will Impact Prenatal Testing

Without abortion rights, basic lab testing applications for those who are or want to become pregnant have new and ominous legal implications.

When the US Supreme Court revoked Roe v. Wade, it did not just take away a woman’s constitutional right to an abortion, it undermined the ethical and medical underpinnings of prenatal and reproductive care. Without abortion rights, basic laboratory testing applications for those who are or want to become pregnant have suddenly assumed new and ominous legal implications for patients and providers alike. While it will take years to unravel these new problems, here is a quick look at what those issues are.

Roe v. Wade and Prenatal Genetic Testing

Approximately three percent of babies born in the US are affected by birth defects due to genetic disorders. About 20 percent of all infant deaths are the result of such disorders. Prenatal tests can detect genetic disorders linked to missing or extra chromosomes in fetal DNA as well as inherited genetic mutations. Accordingly, it has become a routine part of prenatal care, starting at 11 weeks with blood testing and ultrasound to check for Down syndrome and other genetic abnormalities. At 15 weeks, another blood test is done for genetic conditions like spina bifida. At 18 to 22 weeks, ultrasound is used to scan the baby’s bones and organs for anatomical defects. Scans are also performed in the second and third trimesters.

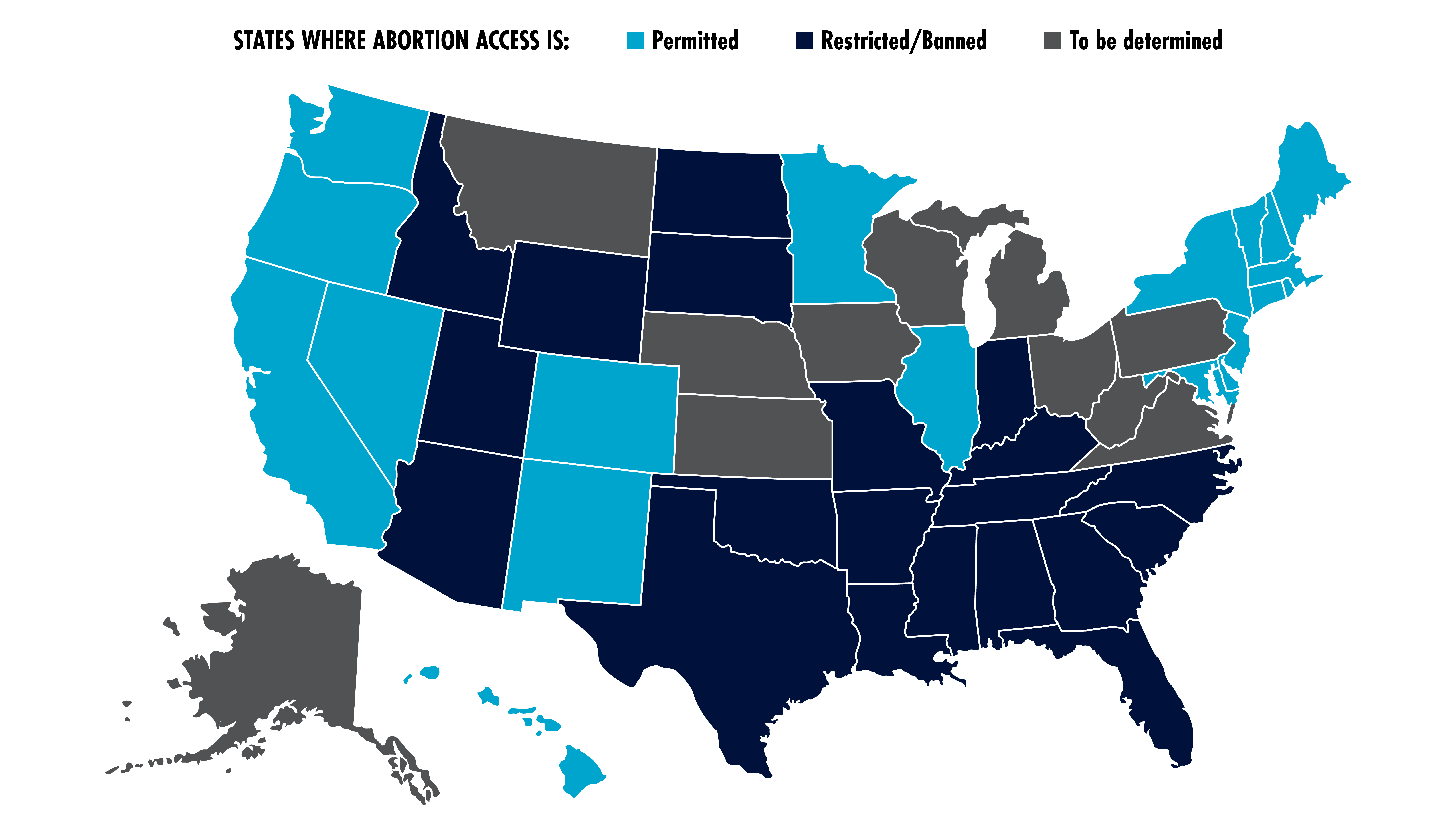

The underlying premise behind all of this testing is that patients may make the decision to terminate their pregnancy based on the test findings. For millions of women around the country, that is no longer true. Now that Roe v. Wade is gone, states are free to regulate abortion rights as they please. Currently, in the US:

- 20 states have laws banning or restricting abortions;

- 19 states permit abortions; and

- 12 states haven’t yet decided whether to permit, ban, or restrict abortions.

In states that merely restrict abortions, pregnancy can be terminated based on test findings. However, some states restrict abortions for anatomical and genetic disorders like Down Syndrome and trisomy 21. That puts doctors and patients in the awkward position of actually benefiting by not knowing of the presence of the conditions for which restrictions are in place, particularly when the fetus has other defects that are not protected.

Another problem is that abortion rights may expire before testing is completed and the results become known. As a result, many patients and providers are doing the tests earlier. But the earlier the scan, the less doctors can see. Thus, for example, certain brain structures, such as the cavum septum pellucidum, might not develop until week 20.

Roe v. Wade and Fertility Treatment

The end of Roe v. Wade has implications for not only terminating but also commencing pregnancy, particularly in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatments in which eggs are taken from a patient’s ovaries and fertilized by sperm in a laboratory. As with prenatal treatment, genetic testing plays a role in IVF to the extent that preimplantation genetic testing (PGT) screening for single-gene disorders such as cystic fibrosis or sickle cell anemia enables parents to select the healthiest embryo.

The concern is that IVF treatments may produce multiple embryos from the same couple. Aborting these embryos could trigger liability in these states, meaning that all embryos produced from fertility treatments would have to be implanted in the patient. This would complicate IVF and likely cause many to forego it altogether.

While patients may opt for methods that produce only one or two embryos, such as intrauterine insemination, the chances of success using this type of approach are roughly the same as conceiving without intervention.

Takeaway

Women who cannot get an abortion in a state have the option of traveling to a state where abortion is permitted to terminate their pregnancy when testing reveals genetic disorders. However, that option is likely to prove costly and burdensome, especially to low-income patients. The other concern is that payors will drop coverage for prenatal tests and PGT screening in states where such information cannot be used as the basis for terminating a pregnancy. These tests and screenings are very expensive and requiring patients to pay for them out of their own pocket would be a body blow for many. The question that insurers will have to wrestle with is whether the savings from dropping coverage of prenatal tests would offset the extra costs that payors would have to incur if the birth of a child with severe medical needs is not prevented.

Subscribe to Clinical Diagnostics Insider to view

Start a Free Trial for immediate access to this article