Laboratory Genetic Counselors: A Valuable Investment

As the field of genetic testing grows, genetic counselors can help labs meet patients’ needs and keep up with new developments

Demand for genetic testing is growing by leaps and bounds—and so is the complexity of that testing. To keep pace with these needs, many genetic counselors are leaving the clinic and moving into lab-based roles where they advise on appropriate tests, interpret and report on results, and liaise between labs, clinics, and patients. The importance of this expert input might seem clear, but many labs are hesitant to consider employing laboratory genetic counselors—and even those who do may face pushback from administrators or institutions who question the value of these roles, says lab genetic counselor Megan Maxwell.

A self-fulfilling prophecy

“Institutionally speaking, genetics is not always viewed as a profitable investment,” explains Maxwell, who is manager of genetics operations for University Health in San Antonio, Texas. “I think this is because downstream medical management isn’t always factored in.”

At the moment, genetic counselors are not considered providers under Medicare,1 which means that they can’t be reimbursed for the services they render—although other providers can bill for these professionals’ services. This means that many institutions don’t view genetic counseling as profit-generating. However, Maxwell counters this by placing genetic counseling services in a wider context.

“The downstream revenue an institution can bring in as a result of making correct genetic diagnoses is substantial,” she explains. “For example, if you diagnose a hereditary cancer syndrome, you prompt that patient to bring in their family to be tested. Those who are positive can receive more frequent screening, prophylaxis, and other interventions.” Despite the savings such preventive care can yield over time,2 Maxwell says it can still be difficult to convince managers and administrators of the value of lab genetic counseling—and, because it isn’t seen as a revenue generator, many institutions don’t have these services in place.

“The same thing happens in academic institutions,” she adds. “If healthcare institutions don’t see the value in bringing genetic counselors into the clinical lab, then there are no rotations in which students can learn the discipline.” She emphasizes that training under experts in other fields isn’t enough. “You can’t place a new genetic counselor with a pediatric neurologist and say, ‘Teach them how to do clinical neurology genetics.’ You need a trained genetic counselor there to guide them and teach them how to do our work—and there aren’t a lot of openings for that.”

Institutional obstacles

To alleviate the academic pressure, Maxwell says, she wanted to become a genetic counseling program director herself. “There are quite a few requirements to become a program director for genetic counseling programs,” she explains. “I understand that in terms of making sure you have well-qualified people running the programs—and making sure they turn out competent, capable graduates—but one requirement I did not meet was 500 hours of clinical supervision.”

Genetic counselors who work in laboratories—or in industry—may struggle to achieve such requirements because the current system does not incentivize students to rotate with lab genetic counselors. “Students must have 45 clinical cases in their caseload,” she explains, “but in laboratory genetic counseling, you’re not getting clinical cases.” Although Maxwell spoke to accrediting bodies, she was unsuccessful in bringing the requirements more in line with lab genetic counselors’ experience. “I said, given that over 25 percent of us are now laboratory genetic counselors, is this requirement biased toward the clinical side? Are we saying that the only people who could be effective genetic counseling program directors are those in the clinic environment? The response was that 500 hours of clinical supervision would remain the standard for program directorships.”

Developing a new program is no small task—but, although Maxwell had already completed a Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board application, structured a learning pathway that integrated genetic counseling education with other health sciences, and received approval from her institution’s graduate school, the requirements for program directorship put an end to the nascent program. “I have 15 years of experience, but the inflexibility of that single standard prevented me from becoming a program director. That tells you how stringent the requirements are and why there are too few programs—and genetic counselors—to satisfy the existing need.”

Making a meaningful difference

To illustrate that need, Maxwell offers the example of a couple she worked with who experienced two consecutive nonviable pregnancies. “If different genetic testing had been performed after the first pregnancy loss, they might not have experienced the second,” she explains. “If I had been involved when the first baby was born, I would have recommended much more comprehensive testing. Unfortunately, I was only involved after the second pregnancy exhibited the same characteristics—and that’s when the cycle ended and they were able to have a successful pregnancy.”

In the case Maxwell describes, the condition involved was so rare that it would likely not have been discovered even with preconception testing—but the outcome of the first pregnancy would have prompted a lab genetic counselor to test more broadly and could have allowed the couple to avoid a second pregnancy with the same issues.

The future of lab genetic counseling

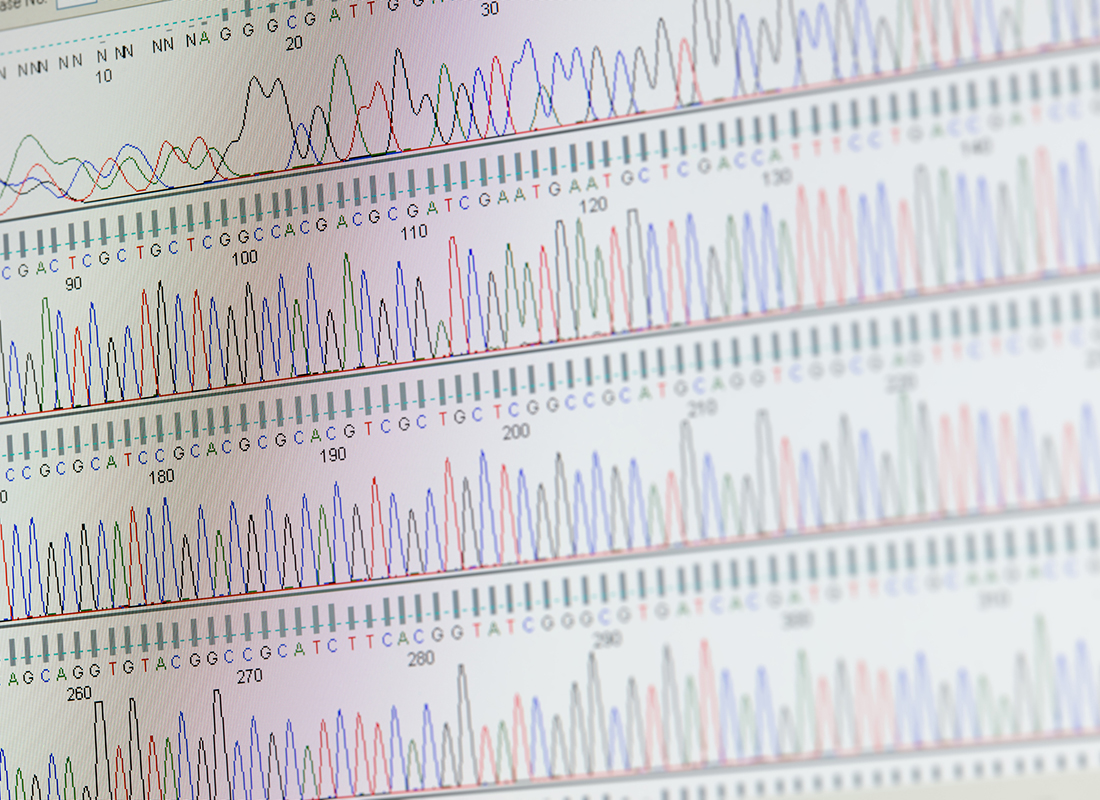

The landscape of genetics as a whole is rapidly shifting. Maxwell emphasizes that, prior to large-scale sequencing technologies, genetic testing was more straightforward. “In situations where gene-disease associations were known, the path was pretty clear,” she says. “If you came to me and you had breast cancer—or your personal or family medical history were indicative of hereditary breast cancer—I would test you for BRCA1. So it used to be quite straightforward and people got comfortable with that.”

But high-throughput sequencing changed the game. “Now we’re finding novel gene-disease associations and new variants, so genetic counselors are having to put their thinking hats back on. It has really become a practice again—and, as with any medical practice, there’s not necessarily a clear formula for any given patient. You have to work through the thought experiment on your own to determine what’s best.”

It’s in situations like these that laboratory genetic counselors are most crucial; their expertise can help other healthcare providers determine which tests are necessary, interpret the results of the tests, and make care plans based on those interpretations.3,4 As genetic testing becomes increasingly complex and in demand, labs that value genetic counselors’ contributions to addressing tricky problems—from diagnostics to test utilization management—will be ready.

References:

- American Society of Human Genetics. Improving Access to Genetic Counselors through the “Access to Genetic Counselor Services Act.” May 20, 2022. https://www.ashg.org/publications-news/ashg-news/improving-access-to-genetic-counselors.

- Ratushnyak S et al. Cost-effectiveness of cancer screening: health and costs in life years gained. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6):792–799. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.027.

- Christian S et al. Defining the role of laboratory genetic counselor. J Genet Couns. 2012;21(4):605–611. doi:10.1007/s10897-011-9419-0.

- Waltman L et al. Further defining the role of the laboratory genetic counselor. J Genet Couns. 2016;25(4):786–798. doi:10.1007/s10897-015-9927-4.

Subscribe to view Essential

Start a Free Trial for immediate access to this article